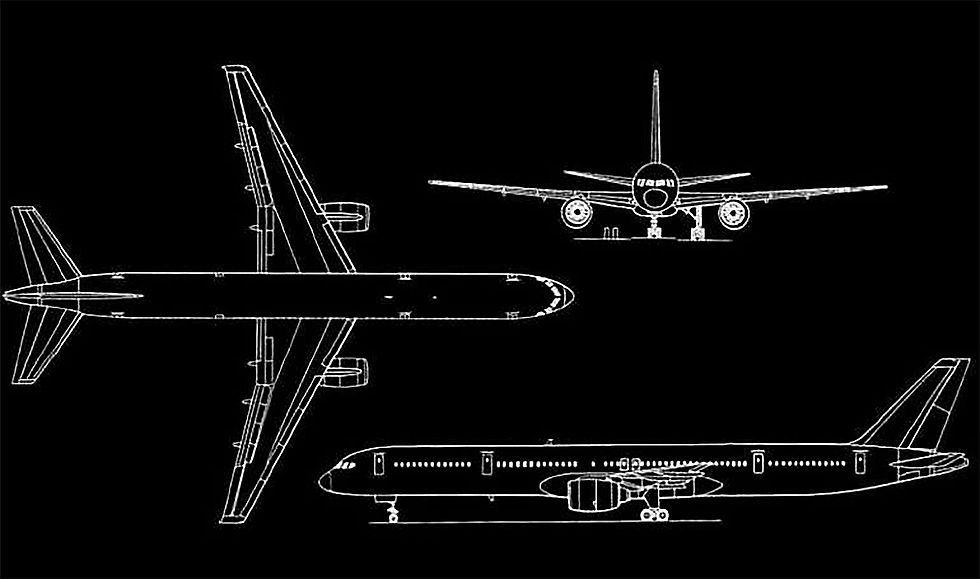

Boeing 757 – Boeing’s Forgotten Gem

- Garth Calitz

- 3 days ago

- 6 min read

By Rob Russell

In the early 1970s, following the successful launch of the first wide-body airliner, the 747, Boeing began looking to further develop its narrow-body 727. Designed for short and medium-length routes, the trijet was the best-selling jetliner of the 1960s and a mainstay of US and European airlines.

Studies focused on improving the 189-seat 727-200, the most successful variant. Two approaches were considered: a stretched 727 (to be designated 727-300), or an all-new aircraft code-named 7N7. The former was the cheaper option - a derivative using the 727's existing technology and tail-mounted engine configuration, while the latter was a twin-engine aircraft which made use of new materials and improvements to engine technology, which had become available since the development of the 727 series.

United Airlines was very much in favour of the 727-300, which Boeing was poised to launch in 1978. Boeing was attracting interest in the 7N7 with features that included a redesigned wing, under-wing engines, and lighter materials, while the forward fuselage, cockpit layout, and T-tail configuration were retained from the 727. Boeing planned for the aircraft to offer the lowest fuel burn per passenger-kilometre of any narrow-body airliner.

On August 31, 1978, Eastern Air Lines and British Airways became the first carriers to publicly commit to the 7N7 when they announced launch orders totalling 40 aircraft for the 7N7-200 version. These orders were signed in March 1979, when Boeing officially designated the aircraft as the 757.

The 757 was intended to be more capable and more efficient than the 727. The 757's higher thrust-to-weight ratio allowed it to take off from short runways and serve airports in hot and high conditions with higher ambient temperatures and thinner air, offering better take-off performance than that offered by competing aircraft.

As development progressed, the 757 increasingly departed from its 727 origins and some features from the 767, which was several months ahead in development. To reduce risk and cost, Boeing combined design work on both twinjets, resulting in shared features such as interior fittings and handling characteristics. Computer-aided design, first applied on the 767, was used for over one-third of the 757's design drawings. In early 1979, a common two-crew member glass cockpit was adopted for the two aircraft.

The 757 cockpit area was widened and dropped to reduce aerodynamic noise by six dB, to improve the flight deck view and to give more working area for the crew and for greater commonality with the 767. Cathode-ray tube (CRT) colour displays replaced conventional instruments, with increased automation eliminating the flight engineer position, common to many three-person cockpits. After completing a short conversion course, pilots rated on the 757 could be qualified to fly the 767 and vice versa, due to their design similarities. That became a strong selling point and many airlines were interested in that.

Despite the successful debut, 757 sales remained stagnant for most of the 1980s, a consequence of declining fuel prices and a shift to smaller aircraft in the post-deregulation U.S. market. In the late 1980s, increasing airline hub congestion and the onset of stricter U.S. airport noise regulations saw a turnaround in 757 sales. From 1988 to 1989, airlines placed 322 orders, including a combined 160 orders from American Airlines and United Airlines. By this time, the 757 had become commonplace on short-haul domestic flights and transcontinental services in the U.S. and had replaced ageing and fuel-guzzling Boeing 707s and 727s.

In part due to a lack of research and passenger resistance, the 757 was not used intercontinentally; it was believed that you needed at least three engines to fly over water. Ironically, in the 21st century, the 757 would have been perfect for the smaller routes, linking Europe and America.

The rise of the low-cost carrier (LCC) model during the 757s production was also a contributing factor to airlines changing their approach to the 757 and rather electing to go down the 737 road. The 757’s mid-range niche didn't quite suit their operating requirements. Instead, airlines like Ryanair and easyJet were placing massive orders for other narrowbodies as the industry trended towards smaller, more fuel-efficient planes, i.e., the new generation B737 -800s and nowadays the Max series and Airbus A320 series.

While the 757 program had been financially successful, declining sales in the early 2000s threatened its continued viability. Airlines were gravitating toward smaller aircraft, now mainly the 737 and A320, because of their reduced financial risk. Customer interest in new 757s continued to decline, and in 2003, a renewed sales campaign centred on the 757-300 and 757-200PF yielded only five new orders. In October 2003, following Continental Airlines' decision to switch its remaining 757-300 orders to the 737-800, Boeing announced the end of 757 production. Several other airlines were to follow Continental Airlines in the move to order the 737-800.

The Boeing 757 was developed in the era of newer modern generation aircraft, with the emphasis on economy and wide bodies. The 767, from which the 757 shares many common design features, was the go-to twin-aisle short and medium-range aircraft. Passengers did not want the single aisle and after getting used to the B747 and other such wide bodies, demanded that the airlines move to twin aisles. This was also seen in the rapid growth of the Airbus A300 and its subsequent replacement, the A330.

However, economics determined where aircraft design was going and on the thinner and more marginal routes, airlines were returning to smaller single-aisle aircraft. The much-upgraded B737 and A320 started to come into favour with the airlines. Newer engines and newer flight systems allowed for dramatic increases in range and nowadays the A321 NEOs and variants of it, as well as the B737 Max series, are seeing these aircraft operate on routes of up to 8 hours – i.e., across the Atlantic linking America and Europe, exactly the routes for the which the B757 was designed for and proved so popular on.

The Boeing 757 wasn’t replaced because it was bad; it was replaced because it was too capable for where airline economics were heading. The 757 had excess thrust, brutal climb performance and payload-range margins that modern narrow bodies simply don’t match. It could operate from short runways, hot-and-high airports and still fly long sectors with a serious payload. That wasn’t inefficiency; it was performance excess. But airlines stopped paying for that. Airline executives were more interested in the bottom line of their bank balances.

The 757 was designed in an era where aircraft were expected to handle the worst day, not just the most common one. Modern replacements are optimised for average conditions, not extremes. They burn less fuel, but they also give up many things which the airlines decided they could live without. This is where the bean counters ruled the roost. The 757 wasn’t beaten by something better. It was sidelined by something cheaper to operate.

That’s why it still has no true successor. That’s why pilots still talk about it. And that’s why operators quietly miss it on the days when performance actually matters and you don't have to worry if you have enough fuel on board to get to your destination and diversion.

The uncomfortable truth: Aviation didn’t outgrow the 757. The bean counters signalled its death knell.

People are still asking if Boeing erred in stopping the 757. Clearly, a great aircraft it was, just built too soon. Boeing elected to expand and develop the B737 series after industry pressure. We all know the problems that Boeing have been having with certification of their Max series. Ironically, Boeing are talking about a new aircraft to replace the B737, when they actually had one in their stable. Maybe the time has come to bring it back, updated and with 21st century avionics, engines and cabin layouts. It can only be a winner!

One thing is for sure - Airbus is smiling - their new generation A320/1 NEO long-range series aircraft is filling the exact market the 757 would have been perfect for and Boeing has yet to come up with a suitable competitor.

Key Specifications Boeing 757 Typical Passenger Version

• Length: 155 ft 3 in (47.32 m)

• Wingspan: 124 ft 10 in (38.05 m)

• Height: 44 ft 6 in (13.56 m)

• Cabin Width: 11 ft 7 in (3.57 m)

• Max Takeoff Weight (MTOW): ~255,000 lbs (115,770 kg)

• Empty Weight: ~127,520 lbs (57,894 kg)

• Max Range: ~3,900–4,700 nm (7,222–8,700 km)

• Cruise Speed: ~525 mph (844 km/h)

• Service Ceiling: 42,000 ft (12,800 m)

• Engines: Rolls-Royce RB211 or Pratt & Whitney PW2000 turbofans

Cargo (757-200F Freighter Version)

• Payload: Up to 72,210 lbs (32,755 kg)

• Main Deck: 15 positions for 88"x125" containers/pallets

• Lower Hold Volume: ~1,830 ft³ (51.82 m³)

Comments